“How much does microfilm scanning cost?” is one of the top questions we receive from people who contact us about their projects. There are plenty of other factors that go into making a successful project, and price isn’t the only thing that will influence your decision. However, we’re not naive and we know that price is a major factor for any purchasing decision! Though it might not be the only thing that matters, the price of scanning will give you the starting point you need to see if you’re even ready to start.

If this is the first page you find when you look for microfilm scanning rates, or you’re just checking a few different sites to make sure you’re not getting the wool pulled over your eyes, we want you to get a feel for microfilm scanning prices and some items that can affect the cost of your scanning project. Until we know about the specifics of your project, we can’t give you a final answer about the price other than “it depends.”

One of our other pages, How Much Does Microfilm Digitization Cost?, is an overview of general scanning fees for the various microform types (microfilm, microfiche, and aperture cards). In this article we’re specifically discussing microfilm and will give you some info about the things that can influence film scanning rates.

If you’re more of a video person, click below to watch our video on:

Microfilm Scanning Costs (Part 1 of 3)

General Microfilm Scanning Price

As we mention on our other page about scanning rates, here’s a simple place to start:

$20 – 40/roll

Easy, right! This is a ballpark price you can use to figure out how much your project might cost you. There are numerous other factors that can make this price go up or down (keep reading!), but with this you can quickly see some ranges that you could be paying to have your film scanned.

Cost Factors

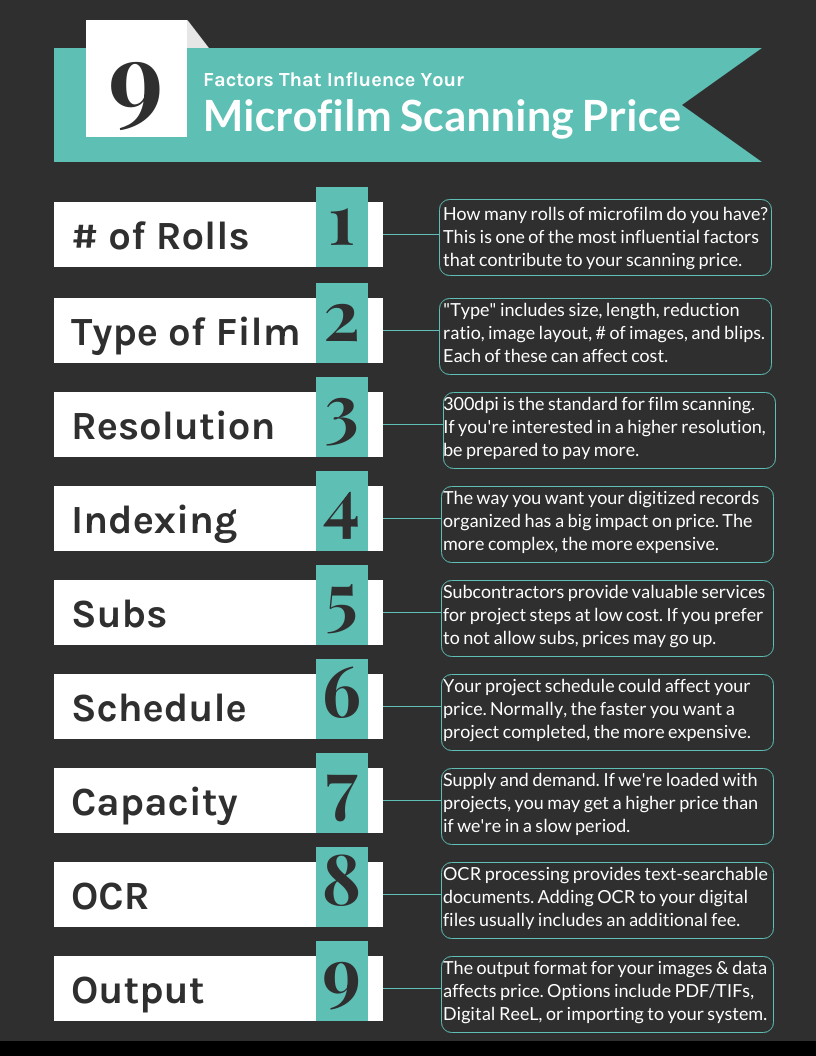

After seeing the $20 – 40/roll price range I’m sure you’d rather we just put an end to this post. However, there’s plenty more that goes into microfilm scanning: number of reels, the type of microfilm, resolution, your indexing requirements, project timing and schedules, and more.

Let’s take a look at each cost factor and see what that can mean for you.

Number of Rolls

The (almost always) first question we ask is “can you tell me how many rolls of film you have?”

Knowing how many microfilm rolls you’re going to convert will give us a high-level scope of your project. The number of rolls isn’t the only thing that matters, but it’s one of the biggest. The difference between scanning 100 reels and 2,000 reels is significant, so having that initial baseline lets our folks start with a volume-based price.

For example, if you call and say you have 100 rolls of film, your starting price will be on the higher side, around $40/roll.

If you call and say you have 2,000 rolls, you’ll be on the lower side, around $25/roll.

You may be thinking, “alright! I’ve got 1,000 rolls so my price per roll is about $30. That means my total project cost will be $30,000. And I’ve got the budget, let’s roll!” (pun intended)

You’re partly right. When you came up with the $30/roll price, that’s not bad. We’d probably say the same thing, so good job with the estimate. What comes after that initial estimate is the adjusting and tweaking to see what the final price will be. The next few sections will cover this in detail.

Last thing for this part: if you have a small number of rolls (up to a couple hundred), counting them isn’t too difficult. When you get to 500+ rolls it might start getting harder to really figure out how many you have, so we put together an article that can help you come up with your count. Go to our page “How Much Microfilm And Microfiche Do I Have?” and scroll down to the part that describes microfilm.

Type of Microfilm

“Type of microfilm? I have microfilm … what else is there?”

If all microfilm were the same, life would be simpler for everyone that works with it. Since there are multiple types, though, we have to dig down to get more specific. If you’re not sure what type of microfilm you have, go here and take a look at the pictures to verify which you have.

Size

The most basic differentiation of microfilm types is the size of the film itself. There are two sizes, 16mm and 35mm.

16mm film is typically used for office-sized documents (8.5×11”) and the physical film is 5/8″ wide.

35mm film is typically used for oversize materials such as newspapers, oversized books, and engineering drawings, and is about 1.5” wide.

Interestingly, your price won’t really change just based on 16mm or 35mm. They’re pretty much the same for us to scan, even though they’re completely different sizes.

Length

Microfilm comes in different lengths, either 100′ or 215′.

A reel of 16mm microfilm can be either 100’ or 215’ in length. 100’ film is called “thick” film because it’s actually a bit thicker, literally, than the 215’ film. And since 100’ is called “thick,” 215’ film is called “thin.” Genius, we agree.

A reel of 35mm film will only come in the 100’ variety.

As we mentioned above in “size,” 16mm and 35mm both come in 100’ length; that’s why your price probably won’t differ if you have 100’ film. If you have 215’ film, you can expect your price to go up at least 50% (if your 100’ price is $30, your 215’ price will be at least $40). There’s twice as much film to scan!

Reduction Ratio

Reduction ratio is the magnification level that the microfilm was originally photographed. In other words, it’s the number of times that the image of the original record is reduced to fit on the microfilm. To be extra technical, the correct term is “optical” reduction ratio because the image is reduced optically (naked eye) and not digitally. It’s an exact representation of the original, just smaller.

16mm film normally comes in at a 24x reduction ratio. So if you’re looking at a roll of film containing standard office docs, like finance documents, the image you’re seeing is 24 times smaller than if you were holding the actual document.

35mm film reduction ratio is usually between 9x-17x. 35mm has more variation in reduction ratio because the types of records photographed can differ in size more greatly than 16mm film.

The reduction ratio of film doesn’t usually come up as a pricing issue, because most film was created in a fairly consistent way. But you might see a price change if instead of the standard 24x reduction on a 16mm roll, your film is 48x. That means that twice as many images can fit on that roll of film, which will require more effort to process and could influence your scanning price.

Image Layout

Microfilm images can be arranged in various ways depending on what records were photographed, who did the filming, and the reduction ratio used to photograph the original documents.

16mm simplex film is microfilm with single images side-by-side to each other – the images go from 1 to 2,500 right next to each other. This is the simplest and most common image layout.

16mm duplex film is microfilm with two images across the width of the film – the images are double stacked within one frame on the roll of film. This is normally used when there’s a left/right or a front/back to a document so that one page is in the same frame on the microfilm roll. The order of the images is usually 1,2,1,2 (top to bottom, left to right).

16mm duplex microfilm

16mm “duo” film or “serpentine” film is rare, and it’s when the images are arranged in such a way that it looks like duplex film, but it starts on the top of the film, and goes 1,2,3,4… left to right then actually snakes around at the end of the roll (hence, “serpentine”) and comes back on the bottom. The last image on the roll ends up next to the first image. Again, very rare.

35mm simplex is microfilm with one image per frame, 1 to 1,000 left to right.

35mm simplex multi-image is when one 35mm frame will have multiple images in it. It’s not necessarily “duplex” or anything like that, because there really isn’t a term for it. What happens is that a 35mm image is created but instead of only including one image of a record, such as an open newspaper, multiple smaller images are shot as one frame.

The image layout on your film might not affect your price because sometimes the layout doesn’t matter and the scanner will capture what’s on the film regardless of layout. The image layout is more of an indicator of the number of images that will likely be on your film, as described in the next section.

Number of Images

The number of images on a roll of film is as various as the number of grains of sand on a beach. Unless you want to actually count out each image on every microfilm roll you have, you can just use the general numbers here.

16mm, 100’ simplex film will have ~2,500 images.

16mm, 215’ simplex film will have ~7,000 images.

16mm, 215 duplex film will have ~10,000 images.

35mm 100’ film will have around 800 images on it, maybe up to 1,000 images.

Remember, these are baseline numbers. We’ve scanned 16mm 215’ duplex film that had almost 20,000 images on it. And occasionally we’ll see 35mm film that has multiple images per frame – instead of filming something like a large book, there are multiple documents in the frame, such as three pages laid out next to each other but captured in the same photograph. This would bump up the image count.

The more images a roll of microfilm contains, the more work is required to process the roll. So, if you have a 16mm film with 2,500 images/roll, your price will be different than if you have 16mm film with 5,000 images/roll.

Blips

Blips are tags at the bottom of a roll of microfilm, below the image, that indicate the location of an image on that roll by marking the frame number.

Single level blipped film is film in which all the blips are the same size. If you’re looking for an image and the index tells you the blip is on frame 379, you’d go to the roll and find the 379th blip and voila! There’s your image.

Double level blipped film is film in which most of the images are marked by normal blips, and certain images have a “double” blip, which is a larger tag to clearly identify the marker. Double blips usually mark the start of a document. For instance, if you’re looking at court case film and the film is double blipped, you might have the first page of each case file marked with a double blip. To find that case, you’d check the index, find the blip number, then go to the roll and locate the double blip. Once you find the double blip you’d be at the start of the case file.

Double-blipped microfilm

Blipped film can affect price both up and down. If your film is blipped and you want files to be named according to blip/frame location, or you want to be able to search by blip in an application, that can bump your price higher. On the flip side, if you just want to know where the blips occur so you can cross-reference your images with an index, that could drastically reduce your indexing cost compared to naming individual files.

Resolution

Resolution is the number of pixels per inch (PPI) that will be used to create an image. Although the correct phrase is “pixels per inch (PPI),” the term “dots per inch (DPI)” is the common way of describing resolution because DPI came from photography before pixels were used in digital imagery.

300dpi is the standard of the digital scanning world. 99% of microfilm conversion projects that we do are scanned at 300dpi.

You can pretty much ask for any resolution from 150dpi – 1,000dpi, but it’d be a request out of the ordinary.

If you decide to have your film scanned at a resolution higher than 300dpi, you can expect your fees to increase. There isn’t a hard and fast correlation between resolution and price, but as you increase the resolution requirement, the actual scanning takes longer because of the additional pixels necessary to create the images. The files also become larger with more pixels. Since the scanning is slower, it takes longer to do the same amount of work that’d be required of 300dpi scanning, and that can mean a rate increase to compensate for more work.

Indexing Specs

The term “indexing” is sort of industry speak in the document management and scanning world, and other names for it include “keying,” “cataloguing,” “naming,” and “organizing.” They all mean the same thing: once your microfilm is scanned and digital, how do you want us to name the files so you can find them later?

Next to the number of rolls you have for your project, indexing is usually the next most critical piece of your scanning project because of the influence it has on complexity and pricing.

If you’re curious and want to read more in-depth about indexing, head to our article “The Wild And Wacky World Of Indexing” to get some more knowledge.

For our example, we’ll say you work at a police department and you have 450 16mm rolls of non-blipped simplex microfilm (with everything you’ve learned about film, we expect you to know this!). On the film are police reports and you’re interested in converting the film into digital images and loading them to your current records database. When we ask how your files are organized in the database, you say that it’s by the report, and that the report number is the way they’re indexed and located.

First, we’ll start with just the scanning – for 450 rolls, we’ll say scanning your film is about $35/roll. Right off the bat your project might be around $15,000 or so.

Next is indexing. Police reports are usually 3-20 pages; we’ll use 10 pages as the average. And we’ll assume the police report number is a six-digit number. So if a 16mm roll of film has 2,500 images, and a report is 10 pages long, that’s 250 reports on one roll of film. With your 450 rolls, that’s 112,500 reports! To match the database you’re using and import these files from the microfilm, we’d have to key around 112,500 reports. That’s a lot of index points. Luckily, the report number is just a six-digit number so it’s not too extensive, but 112,500 report numbers is still a lot.

Since these records are criminal justice information and definitely sensitive, we can’t just do whatever we want with them! If you want each report indexed, our folks would need to look at every single image on the film to first identify an image that has a report number, then we’d have to index the report number and match it to the digital file. Just looking for a report number means we have to look at 1,125,000 images (450 rolls x 2,500 images per roll). To get this done properly (meaning not sending it out to someone who’d not supposed to have the data) you’re looking at somewhere in the $0.20 – 0.40 / report number range just for indexing. At the low end, that’s an additional $50/roll on top of the scanning, so you’re now at $85/roll for a project price of around $39,000. That’s a big jump from the original $15,000!

Before providing a different option, it’s critical to note here that if you require the microfilm to be indexed at the report level so you can get it into your database, then that’s that. There are ways to tweak pricing and adjust to try and fit your budget, but if you need it, you need it.

Instead of indexing at the report level, why not just index at the roll level and use your film just as you do now, but in digital form? If we indexed at the roll level, you’re still looking at about $15,000 for your project. Especially if you’re not using your film all the time because these reports are older, then is it really worth it to spend almost $40,000 to have extremely detailed indexing? Maybe not.

Subcontractors

Are you ok with your scanning partner using subcontractors?

We can’t speak for every scanning and conversion company out there, but we’re pretty confident that the vast majority use subcontractors for various activities in their companies. It makes sense, because to keep costs down it’s sometimes more viable to use another agency instead of your own employees. Even we are hired as subcontractors for projects! Other scanning companies might not have the ability to do some of the work on a project, such as microfilm scanning, so they hire us to help out.

“Subcontractor” often has a negative connotation when you’re a buyer, because you’re wondering “where are you sending my stuff?!” We know where you’re coming from and understand the concern. Using subs allows companies, including us, to lower our costs which means …. lower prices for you! We’ve seen it before when a client doesn’t want to have subs on their project. If the original price with subs was $20,000, the new price without subs could be double that or more. We’re good to go either way, but we hope you’re prepared for a big difference in your price.

We use subcontractors at various stages in our scanning processes, and only on certain projects. Also, we have business associate agreements in place with our subs and include them in our internal security audit each year; we don’t work with just anybody. Another key point is that just because we might be using a sub on a project does not mean that the entire project goes to them. Usually, just a very small portion of the project goes to our subs, and we protect your data through various means when we include them on a project.

Some examples of how we use subs include:

Image Framing

Checking low-resolution, illegible images to “frame” the images so that the data is captured and can be converted into a PDF or TIF, and to ensure the images are clickable in Digital ReeL.

Indexing and Data Entry

Capturing data fields to index and name the digital files. This might include the entire indexing spec or just a part of it.

Document Identification

Looking through images to identify certain features, such as a flasher at the beginning of a file or a stamp that indicates a specific record.

Quality Assurance & Quality Control (QA/QC)

We do many of these processes using our own employees and technology, but we might still use a subcontractor to check our work or a percentage of it. In this way having subs check our work helps minimize mistakes and errors on our film scanning projects. Take a look at our QA article to learn more about this topic.

If you’re not comfortable having subcontractors work on your project, no problem. Just be aware that it’s usually less expensive when subcontractors are allowed than when they’re not.

Project Schedule

The project schedule you request might not create a massive difference in the price we give you, but it’ll probably change it at least a little.

The sibling of your project schedule is our project capacity (see next section below), so they’ll influence each other. To keep things simple let’s pretend that our capacity for new projects is always consistent, so it’s a moot point for this example.

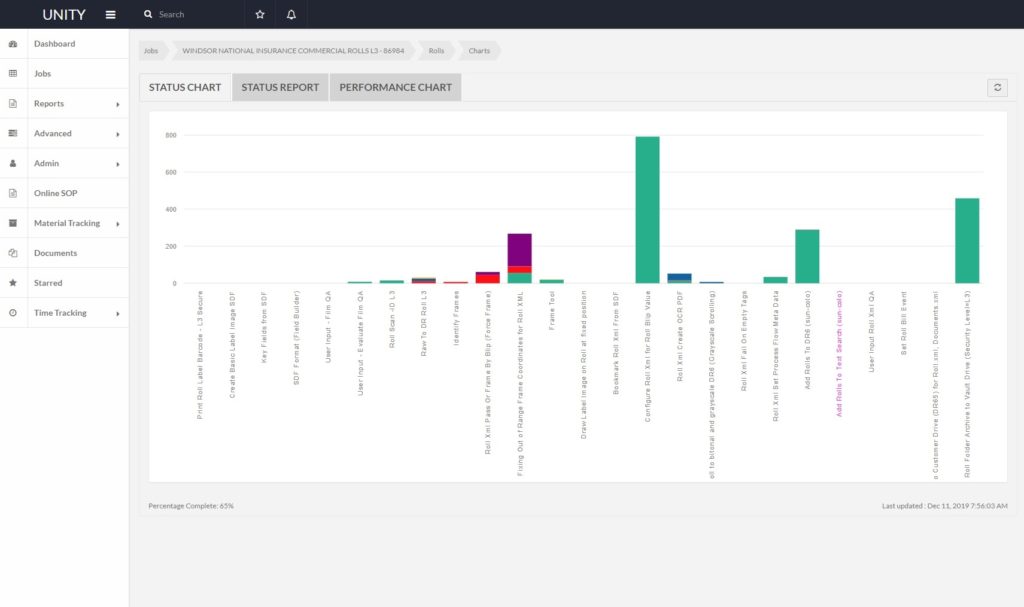

You have 3,000 rolls of 16mm 100’ simplex microfilm that you want to get scanned, and you ask us the price. At that number of rolls, you’re in the $25/roll range, which puts you at $75,000 total. Now, when we give you this estimate we’re usually thinking that the project isn’t a rush and we’re on a “standard” scanning schedule. A 3,000 roll project will take about 3-4 months, depending on testing, indexing specs, and the cadence you’d like to proceed with (not every client gives us all of their film up front; usually larger projects are done in batches).

An image of a “process flow” – all the steps in this particular microfilm scanning project.

If this was your project and you asked it to be completed in half the time as is usually required, you can imagine that it might cost more!

If you tell us that you need the project started and completed within one and a half months, this changes things. We’ll have to prioritize your project, shift around other project commitments and schedules, and get your project going fast. Now you’re probably more in the $30/roll range, for a total of $90,000. Again, this is assuming all other things affecting our operations never change. There’s always more than one piece to a puzzle, but we wanted the example to be simple. Is it worth $15,000 to you to have the project done in half the time? That’s up to you to decide.

Not sure how to schedule your project? Read our post about reverse engineering your project to maximize your success.

Capacity

Humans prefer stability and knowing what’s coming at them, and we try to create this for our project team and operations folks. But change is inevitable, and it’s the ability to adapt to change that separates the survivors from the extinct.

We’d love to have a solid, unchanging, known project schedule, but our project capacity is forever changing, month to month, week to week, even day to day! To adapt to the constant change, our project and operational leaders meet every week to discuss completed projects, work-in-process, and incoming jobs. Priorities are confirmed, adjusted, or flipped, stalls are discussed and solutions created, and gaps in inventory are identified and relayed to the sales team to keep the machines running.

How does our capacity affect your price? Supply and demand, really. If we’re loaded with current projects and have scores more lined up ready to start, we don’t necessarily need an additional project, yours, at this moment in time. We’re not saying we don’t want to work with you, it’s just a matter of timing. If we’re full up and you need your project started immediately, you’ll probably pay a higher price than if you’re okay with holding off until we get through some of our current projects.

On the other hand, if you contact us for film scanning and we’re at a stage where we don’t have many microfilm projects in house or on the way, you’re probably going to get a slightly lower price than normal – we don’t want our scanners idle, so we’re willing to take a little off the top to get your film now!

It’s like buying skiing clothes: if you buy in summer, you’re probably going to spend way less than if you bought the same stuff in winter!

OCR

When you get your digital images back, do you want to be able to search for words and phrases? If you do, then you want OCR text search. OCR, or Optical Character Recognition, is what enables you to turn standard image-only files into searchable data. For more detail, take a look at our article about OCR.

When you have your microfilm scanned, the default format of the electronic images that are created is “image-only,” which means that the image isn’t searchable. Once you say you want searchable data, that triggers the OCR process.

OCR is normally an automated procedure. When one of our clients requests OCR for their project, a step is added to their project process flow in which the digital images are ingested into our OCR engines, creating searchable files.

Since the process is done “automatically” by computers you might think that it’s free, but that’s not the case. There are always limits to technology, and although a human isn’t doing the OCR individually, we only have so many OCR engines to process images. Because of that, there may be an increase in your project price to add OCR. And like we discussed in the section about capacity, sometimes we’re more backed up with OCR projects than others – if we’re low on images to process through OCR, we might want your project more and be able to provide you a lower price.

Image & Data Output

When you decide to scan your microfilm, you’ll need to have an end-goal in mind of how you want to access your images and data. The three options you’re able to choose from are a “traditional” output, the “Digital ReeL” cradle-to-grave solution, and “your current electronic records application.”

Traditional

Traditions are great. Without them, every day would be chaos because we wouldn’t have any baseline or routine to guide are lives from. When it comes to microfilm digitization, we define a traditional conversion as a scanning project in which you receive standard PDF, TIF, or JPG files once it’s complete.

This is probably what about 95% of folks who contact us think all film scanning projects are, and we’re not going to fight it or try to change your mind; that’s why we call it traditional! Getting a request for PDFs is the majority of first interactions, because we’re all so used to using PDFs in our daily lives.

When we run a traditional microfilm conversion project for a client, we’ll normally deliver the files (PDF, TIF, JPG) in one of two ways:

- Single-page files in roll-level folders

Each roll will be converted to a digital “folder” with single-page files named sequentially in that folder. Imagine a Windows-style folder named by the roll label (“Roll 235”) with hundreds or thousands of images in that folder named 0001.PDF, 0002.PDF … 2500.PDF.

- Multi-page files indexed by roll

Each roll will be converted into a multi-page file and we’ll name it by the roll label. You’ll see a file such as “Roll 235.PDF” and when you open that file, it’ll be a 2,500-page PDF.

Digital ReeL

Digital ReeL is a hosted application that was created for microfilm records. The primary use for Digital ReeL is as an archival records management system, not necessarily a go-forward platform for day-to-day scanning and importing. The interface virtually replicates your microfilm so that you can visually verify all images were captured, and you’re able to search for documents using index searches and global text search (if you OCR’d your docs).

Yes, Digital ReeL is an application we created, and we include it here because it’s distinct from the other two options (traditional output and importing into your current records database).

When it comes to fees, Digital ReeL is actually about the same as a traditional scanning project. Because it’s an in-house application, we control the environment and can keep costs down, instead of being a middle-man selling another product. And if our costs stay down, yours do, too.

Your current electronic records application

If you already have an electronic database of records, you might not want to purchase a new one (such as Digital ReeL) or just get some PDF or TIF files on a USB drive. You’ll probably want to import the newly digitized images into your existing system so that you can have a single access point for your legacy, current, and future records.

Granted, if you’re importing to an existing application you’re probably still going to want PDF, TIF, or JPG files. But the last piece of the puzzle is that you’ll want them formatted for import and auto-population into your system. So it’s kind of like a traditional conversion 2.0.

What your project will cost you will depend on the complexity of your system and the fields required to import the images and data once they’re scanned. The more complex, generally the higher the fee.

Conclusion

So, after all you’ve read and learned we’re assuming your question still stands:

How much does microfilm scanning cost?

And we hope that you understand our answer, at least for now:

It depends.

Next Steps

Reach out to us today! Click the “Get Your Quote” button below, fill out the form, and we’ll quickly reply to you to discuss your project.

Further Reading

Now that you know what goes into microfilm scanning prices, below are some other articles about microfilm and digital conversion that can help you understand other parts of the process.

“How Much Does Microfiche Scanning Cost?” is the sibling article that covers microfiche scanning costs. If you have microfiche, check out this article for examples and specifics.

“How Much Does Aperture Card Scanning Cost?” is another post about scanning costs, this one specifically about aperture cards.

“The BMI Microfilm Scanning Process” describes the actual steps we take to scan your microfilm. There’s an infographic included so you have an easy-to-follow visual representation of the process.

‘How To Choose The Right Microfilm Scanning Partner” provides you with our insights into how to select the right scanning partner for you. And yes, we might not be the right fit.

“The BMI 6-Step Microfilm Scanning Process For Small Projects” covers how we handle projects that are on the “smaller” side compared to our normal jobs. If you have fewer than 100 rolls to scan, take a look!